Once people own something (or have a feeling of ownership) they irrationally overvalue it, regardless of its objective market value. People feel the pain of loss twice as strongly as they feel pleasure at an equal gain, and they fall in love with what they already have and prepare to pay more to retain it. For example, scientists randomly divided participants into buyers and sellers and gave the sellers coffee mugs as gifts. Then they asked the sellers for how much they would sell the mug and asked the buyers for how much they would buy it. Results showed that the sellers placed a significantly higher value on the mugs than the buyers did.

Once people own something (or have a feeling of ownership) they irrationally overvalue it, regardless of its objective market value. People feel the pain of loss twice as strongly as they feel pleasure at an equal gain, and they fall in love with what they already have and prepare to pay more to retain it. For example, scientists randomly divided participants into buyers and sellers and gave the sellers coffee mugs as gifts. Then they asked the sellers for how much they would sell the mug and asked the buyers for how much they would buy it. Results showed that the sellers placed a significantly higher value on the mugs than the buyers did.

A variation of Endowment Effect is IKEA Effect: A cognitive bias in which people place a disproportionately high value on products they partially created. For example, in one study, participants who built a simple IKEA storage box themselves were willing to pay much more for the box than a group of participants who merely inspected a fully built box.

Take-away: Consider the Endowment Effect the next time you are in a sale/purchase negotiation. If you are the seller, it may be difficult for you to objectively assess offers that fall below your personalized value of your [beloved vintage car, the house where you brought home your first baby, etc.]. This is why researching objective standards and norms is so important in planning for a negotiation. If you are the buyer, being aware of endowment effect can help you communicate empathy and build rapport, while expressing the objective market fairness of your offer.

Background on our Cognitive Traps series (not our own original research): Social and cognitive psychologists have been interested for decades in how the brain processes information and what that produces in the outside world in terms of behavior. In the 1970’s, two psychologists from Stanford University (Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky) started to study aspects of decision-making: does the rational person made decisions based on innate cost-benefit economic analysis? Their work (called Prospect Theory) created a new discipline of science known as Behavioral Economics, which earned them the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 (Tversky had died in 1996, so technically the prize only went to Kahneman at the time it was bestowed). According to behavioral economics, the Rational Person theory doesn’t take into account all the reasons people behave the way they do. People make decisions relative to a reference point, and that reference point is the status quo – “where I am now.” Kahneman and Tversky categorized their work into a set of common heuristics: shortcuts that the brain takes so that it can make decisions in fast-moving everyday life. But many of these heuristics can also act as cognitive traps in a negotiation, if you aren’t aware of them. Endowment Effect is one of them.

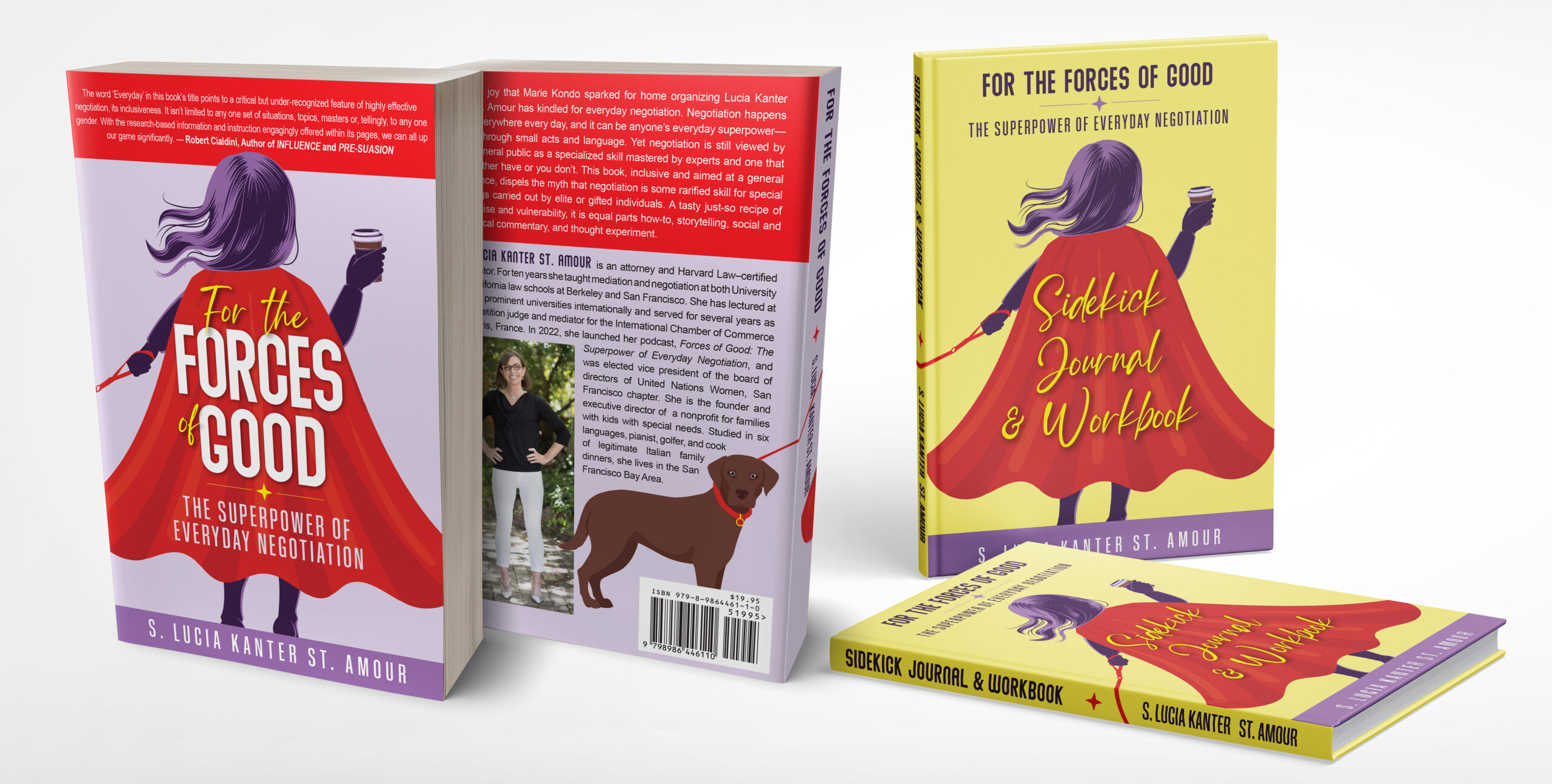

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal