Sep 8, 2020

Abstract: History of the handshake, its societal and business uses, its importance in mediation and negotiation, and what lies ahead now that the handshake has become a casualty of Covid-1.

Abstract: History of the handshake, its societal and business uses, its importance in mediation and negotiation, and what lies ahead now that the handshake has become a casualty of Covid-1.

The handshake: it was our loyal and familiar anchor for millennia. It operated as a widespread social custom to forge political alliances, seal business mergers, and inform telepathic fathers about the “true” character of their daughter’s latest beau. Now rendered verboten by Covid-19, the handshake was at least 2,800 years old, as evidenced by an early limestone dais, carved in the mid-ninth century B.C.E., depicting the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III hand in hand with a Babylonian ally. Historians believe that an early purpose of the handshake was to show that you weren’t holding or concealing a weapon (the up-and-down motion would dislodge a dagger that had been hidden up a sleeve). It has also been used as a way to assert dominance and signal competitiveness. In some cultures, the handshake almost took on the role of a contract.

Throughout history and across many Western cultures, greeting each other with a handshake at the beginning of a negotiation, even if perfunctory, has been an important tool to convey the willingness to cooperate towards reaching a deal – and later to secure agreement on a point. And although a handshake alone does not offer either party sufficient protection should things go wrong (as in Neville Chamberlain’s famous handshake deal with Adolf Hitler over the ill-fated Munich Agreement in 1938), it’s efficient, it’s personal, and it gets things moving. Even before the Coronavirus pandemic, some may have already dismissed the custom as too medieval to be meaningful in the modern, digital world. But famous deals from depictions of Cleopatra to Google (and Elvis in between) would suggest that its longevity and ubiquity was no accident. Remember the 161-day NBA lockout in 2011? It was finally resolved with a handshake deal – one with billions of dollars at stake. At a deeper sub-conscious level, when people participated in the social norm of shaking hands over a deal, they were taking part in an age-old tradition that exhorted them to behave honorably.

But, alas, the Coronavirus rendered the steadfast handshake taboo, even before Shelter In Place orders were mandated. Since then, Dr. Anthony Fauci sounded the death knell in April, when he proclaimed this about our old reliable companion: “I don’t think we should ever shake hands again.”

Thus ends (or at least cryogenically hibernates) the de rigeur, millennia-old global standard for greetings and business. The void leaves us feeling, well . . . a bit empty-handed.

Beyond the handshake, other cultural customs have been abandoned (perhaps for good) as a result of the pandemic. For example, as a person of Italian descent, I greet friends and family in Italy (and Italian friends here in the States) with a quick, alternating kiss on each cheek (called a bacetto). This custom dates back to the Ancient Romans. The French embrace a similar convention harkening back to the French Revolution, when double-cheek-kissing upon greeting someone was introduced. High fives and fist bumps among teammates and colleagues as encouragement or to celebrate a “win” have similarly fallen out of fashion in our brave new world. Without these faithful “old world” social and cultural gestures to serve as punctuation marks, negotiated deals feel incomplete.

So what now? Do we place a hand over our heart as a salutation and departure to bookend our negotiations and mediations? Do we form the peace sign with our fingers? How about a “handshake” button in our widgets, which parties click for agreement, a la YCombinator? Particularly with the increased popularity of Zoom mediations (which are most likely here to stay, is there some talismanic phrase or ritual (one that inspires cooperation, connectedness and commitment, mind you) that we develop to open and close a mediation session? While I don’t have an “aha!” answer, I am confident we imaginative and resourceful humans (and especially mediators) will evolve into a new custom.

In the meantime, perhaps my Italian compatriots will bob from side to side while kissing the air from a 6-foot distance; and high-powered executives, movie producers and real estate moguls still have the backs of receipts and cocktail napkins to seal the deal (as long as they immediately wash their hands).

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Jul 14, 2020

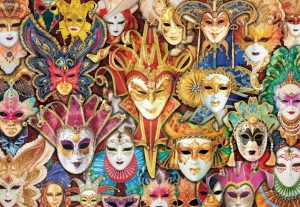

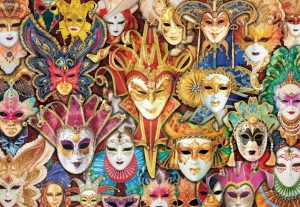

Masks are nothing new. They have been used in rituals and ceremonies dating to 7000 BCE.

Masks are nothing new. They have been used in rituals and ceremonies dating to 7000 BCE.

Two widespread uses of masks dominate history and culture. The first is for festivals and ceremonies. Perhaps most commonly known is the Carnevale of Venice, Italy, rooted in the 13th century. Carnevale is also known as Marti Gras, famously celebrated in New Orleans here in the States. Historically this is the 2-week raucous festival of indulgence preceding the 40- day deprivation period of lent. During Carnevale, the usual expectations of desired social behavior are suspended.

It functions partly as a reversal ritual, allowing the primitive element of human nature to express itself.

The second usage is among legends and heroes: these characters conceal their true identity behind a mask to carry out deeds as vigilantes on behalf of the greater public good. The first examples emerged in the early 1900’s:

Zorro was the alter ego of Don Diego de la Vega during the Spanish colonial period. He defended commoners and indigenous people of California. During that same decade we were also introduced to The Scarlet Pimpernel: chivalrous Englishman, Sir Percy Blakeney, in the Time of Terrors in France.

Garnering a cult-like following in the late 1980’s from the film, The Princess Bride, The Man in Black operated as alter ego for Westley: simple farm boy turned pirate – in love with Princess Buttercup. While clumsily and half-heartedly combatting Westley, the benign giant named Fezzik inquires, “Why do you wear a mask? Were you burned by acid, or something?” Westley prophetically replies, “Oh no. It’s just they’re terribly comfortable. I think everyone will be wearing them in the future.”

These masked figures share certain traits: they have a signature weapon, usually a sword, which they employ with expert prowess. They are physically agile and skilled escape artists. They are intelligent and able to outwit their foes.

Now that masks are mandatory for all, they are used (or not used) as fashion and political statements. The overarching question is this: Hedon or Hero? Will we draw upon our best selves to unite widely, ensure Black Lives Matter, heal deep grief, cultivate diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging? Will we surrender to our more savage nature and breed mistrust between communities; depend racism and hatred? The answer to that is still an individual choice.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Jun 5, 2020

We (Americans and many diverse people in organizations) have borne witness to this moment before: there was a terrible event, we were outraged, we reacted, then it went away. Yet systemic racism hasn’t changed. How can leaders meaningfully respond to racial tragedies? This was the subject of a webinar and Forbes article by the Neuroleadership Institute. To move forward first requires recognition that people are in different places. Then, three critical steps – in this specific order – are necessary to create positive change (relevant to organizations, teams and families):

We (Americans and many diverse people in organizations) have borne witness to this moment before: there was a terrible event, we were outraged, we reacted, then it went away. Yet systemic racism hasn’t changed. How can leaders meaningfully respond to racial tragedies? This was the subject of a webinar and Forbes article by the Neuroleadership Institute. To move forward first requires recognition that people are in different places. Then, three critical steps – in this specific order – are necessary to create positive change (relevant to organizations, teams and families):

(1) Listen Deeply:

Listen so that people feel deeply heard (like they have never felt before): listen to understand (not to respond, to defend, to countermand – or pretending to listen while really just waiting for your turn to talk). At a minimum this means removing obstacles and distractions to listening to others. Even on Zoom, people know when you are listening deeply and when you are not. It is difficult to listen as a leader when you are also feeling anxious and having your own brain’s threat response. Moreover, listening to people with strong emotions can be very uncomfortable (and cause you to feel strong emotions, which means you as the listener need to be mindful and place your brain in a low threat state). We also have a tremendous number of built-in biases that are very difficult to mitigate. Many of them cannot be mitigated. One of them is Experience Bias, which can be reduced by truly hearing diverse perspectives (sitting in someone else’s world. This is very effortful). Another form of distraction is relating so closely to the experience of the speaker that it causes a “me too” reaction and focus on your own story. To really listen and be there in the moment can be draining, but the science reinforces that you must do this well and focus in on the speaker. This means, as a leader, taking care of yourself better than ever so that you can put yourself in the right mental framework to look out for others. On the other side: the experience of being heard is one of the few things that really calms a stressed state of mind. Most of the time we are not tuned in to what others are experiencing in their daily lives.

(2) Unite Widely: But step one isn’t enough. If leaders stop at step one, we will keep having the same conversations and conflicts over and over. For solutions to happen, people need to feel they are on the same team. A deeply rooted process in the brain plays out when humans interact: it is a fairly binary categorization known as “in-group” or “out-group.” The science of this is kind of scary: with every human we encounter, we decide if they are in-group (like us / aligned goals) or out-group (different from us / competing goals). We tend to default to the latter. When someone is an out-group member, we tend to process any information from them in a shallow way. But any information from an in-group member, is processed into thinking your own thoughts – as if you are talking to yourself. Even physical movement of someone in-group or out-group is processed differently (e.g. Black man reaching for cell phone processed by White police officer as reaching for gun). Secondly, we have very little empathy for people in our out-group. This makes us capable of doing very bad things to people who have different goals from us. Another factor is motivation: we are invested in seeing in-group members win; but this is reversed with out-group members. Even when out-group members tell us a positive story, we don’t feel the triumph for them that we do with in-group members. Inclusion means proactively including everybody. The good news is that it doesn’t take much to create an in-group among very diverse people – but the key is identifying a common goal

What are the mechanics of inclusion? We introduce Dr. David Rock’s SCARF model, which summarizes the neuroscience observation that the brain treats social threats and rewards with the same intensity that it treats physical threats and rewards. The SCARF model accounts for five domains of human social experience: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness. These domains also serve as 5 strong threats that the brain tracks over time. When threatened, each one activates the pain center of the brain. So, if you have multiple SCARF factors causing threat, as in the George Floyd tragedy (an accumulation of widespread, systemic SCARF threats over an extended period of time), the situation is explosive. But these same factors also can also be used to unite widely.

Take away: leaders need to find shared goals in an organization, team, or family. When we do that, our differences become diversity mechanisms that help us reach our shared goal. Until we unite around shared goals, we remain in the in-group / out-group paradigm and our differences continue to divide us.

(3) Act Boldly: Vision without action is a daydream; action without vision is a nightmare (as Khalil Smith’s father used to say). We’ve been here before. Why didn’t things change? (1) False promises and failed expectations when an expectation was created to do “big things.” (2) We remained stuck in story-telling, and systemic habits did not change. No big change happens in an announcement. An announcement is a start. But if it doesn’t scare you a little (“we’ve never done that before”), it isn’t truly bold. Bold action is messy, difficult, and resource consuming. But normalcy must be refuted. As Dante Alighieri wrote: “The hottest places in Hell are reserved for those who, in a period of moral crises, maintain their neutrality.”

What are some examples of what organizations can do that is “really bold” (beyond writing a check): (1) Provide free de-escalation training to all law enforcement (The Neuroleadership Institute is doing this); (2) Local governments retraining law enforcement standards and practices for peaceable protests and crowd control; (3) Meaningfully reviewing your organization’s culture for allowing employees a voice, and then improving and building on that; (4) Check your Diversity Training – it might be making people MORE biased, especially if it’s mandatory. (5) Change habits (individually and organizationally). This means, first, figuring out which ones matter; then, following up with a practical plan and working collectively in a way that is impactful to reshape them.

On a parting note: imagine the systemic impact of matriculating a generation of leaders from a young age, who are able to adopt and act upon these principles. Peer mediation in schools is one way to develop a generation of thoughtful listeners and impactful peacemakers who become paradigm shifting leaders.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

May 1, 2020

More and more disputing parties and attorneys are turning to online dispute resolution (ODR) during extended Shelter In Place, and online mediation is most likely the new “normal,” here to stay. It may be reassuring to know that this is not a new trend, and the platform for ODR has been in development and use for many years.

More and more disputing parties and attorneys are turning to online dispute resolution (ODR) during extended Shelter In Place, and online mediation is most likely the new “normal,” here to stay. It may be reassuring to know that this is not a new trend, and the platform for ODR has been in development and use for many years.

Colin Rule has been a pioneer in the field of ODR for over 25 years, and we first met him in the early 2000’s when he was developing the Ebay and PayPal dispute resolution systems, the first large scale ODR platform. In this podcast for the American Bar Association, Colin discusses the origins of ODR, and how it has evolved over the years and is now used by courts with matters ranging from traffic citations, to property tax appeals, to family and employment law cases. Ultimately, all ODR technologies evolve out of face-to-face practices because dispute resolution has historically been a face-to-face experience.

At Pactum Factum, we offer “in person” virtual mediations using Zoom. Pactum Factum Principal Lucia Kanter St. Amour is a mediate.com Certified Online Mediator. Unlike the use of algorithms and other technologies used for simple e-commerce disputes, the “in person” aspect of mediation is quite an important psychological component of the process. Research shows that trust in an experienced mediator is the same whether a mediation participant interacts with that mediator via video or face-to-face (i.e. physically in the same room). After some pre-mediation preparation, we join the meeting as a group for the initial joint session, and then enable Zoom Breakout Rooms (or not – we have other options) for the private caucusing. The beauty of online mediation is it’s versatility: it can be scheduled in smaller chunks than the traditional “one big day” of brick and mortar mediation, and we can blend various modalities throughout the process. For more information about online mediation, visit our Forms and FAQ’s pages.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Mar 1, 2020

Does Shelter In Place make you feel like a prisoner? In game theory, the prisoner’s dilemma is a famous example of why two completely “rational” individuals fail to reach an equilibrium point (unless they figure out how to cooperate). It is a paradox in decision analysis demonstrating that when two individuals act in their own self-interests, they do not produce the optimal outcome. The typical prisoner’s dilemma is set up in such a way that both parties are encouraged to choose to protect themselves at the expense of the other participant.

Does Shelter In Place make you feel like a prisoner? In game theory, the prisoner’s dilemma is a famous example of why two completely “rational” individuals fail to reach an equilibrium point (unless they figure out how to cooperate). It is a paradox in decision analysis demonstrating that when two individuals act in their own self-interests, they do not produce the optimal outcome. The typical prisoner’s dilemma is set up in such a way that both parties are encouraged to choose to protect themselves at the expense of the other participant.

The classic prisoner’s dilemma is set up as follows: Two suspects, A and B, are arrested by the police. The police have insufficient evidence for a conviction, and having separated both prisoners, visit each of them and offer the same deal: if one testifies for the prosecution against the other and the other remains silent, the silent accomplice receives the full 10-year sentence and the betrayer goes free. If both stay silent, the police can only give both prisoners 6 months for a minor charge. If both betray each other, they receive a 2-year sentence each. Each prisoner must make a choice – to betray the other, or to remain silent. However, neither prisoner knows for sure which choice the other prisoner will make. What will happen?

If reasoned from the perspective of the optimal outcome for the group (the two prisoners), the correct choice would be for both prisoners to cooperate with each other, as this would reduce the total jail time served by the group to one year total. Any other decision would be worse for the two prisoners considered together. When the prisoners both betray each other, each prisoner achieves a worse outcome than if they had cooperated

Prisoner’s Dilemma is also an example of a type of Nash Equilibrium, discussed in our February 2018 blog entry.

Take-away: In our quarantine situation (and in negotiations in general), we can achieve a better outcome for all parties by cooperating. This may mean surrendering options and behaviors that would especially benefit each of us individually. In life and in negotiation, ask yourself what your goal is: is it to “beat” the other side? Is it to optimize profits? Is it to build a relationship? Consider the ultimate goal, and assess what “cooperation” means in promoting that goal, and how to communicate it.

Jan 2, 2020

While the list of “important” ne gotiation skills is robust, if I had to pick one above all others, it’s listening – which is both terribly important and terribly underutilized. In the early 2000’s during my initial training as faculty for the Center for Negotiation & Dispute Resolution at UC Hastings College of the Law, I learned a method for teaching Negotiation students cultivated by psychotherapist Judi MacMurray, who granted permission for us to share her methodology. This chapter of my blog is a compilation of her tutorial and my own adaptations and experience with listening over the years. Consider it a step-by-step guide – not just in negotiation, but in everyday life. Like everything else, it takes practice:

gotiation skills is robust, if I had to pick one above all others, it’s listening – which is both terribly important and terribly underutilized. In the early 2000’s during my initial training as faculty for the Center for Negotiation & Dispute Resolution at UC Hastings College of the Law, I learned a method for teaching Negotiation students cultivated by psychotherapist Judi MacMurray, who granted permission for us to share her methodology. This chapter of my blog is a compilation of her tutorial and my own adaptations and experience with listening over the years. Consider it a step-by-step guide – not just in negotiation, but in everyday life. Like everything else, it takes practice:

When I taught the Listening module to law students, I would start the lesson by asking for a show of hands of those who were told as a kid that they’d make a good attorney some day because they were good at talking / arguing. Invariable, several hands shot into the air. Then I would ask how may of them were told they would make a good attorney some day because they were a good listener. In all my years of teaching (in the U.S. and abroad), not a single hand was raised in response to that prompt.

According to psychotherapists, three key traits of good listeners are that they are nonjudgmental, sincere (meaning your “insides match outside”), and empathetic.

Why is this so important?

*Establishes better understanding

*Builds rapport, trust, credibility

*Information gathering: to negotiate a good deal, need to know what the other side wants and needs

*Shows respect

*If other side does not feel heard, they may shut down

*Triggers Reciprocity [see this blog – January 2019)

As Steven Covey wrote: “Seek first to understand rather than seeking to be understood” (though I don’t think he is the originator of that advice. Don’t quote me on this, but I have a vague recollection from studying the Classics at Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Prairie View, IL that this thought originates from Plato’s Republic).

And I have good news: you already know how to do it (but most likely haven’t been practicing it). This simple model is based on ordinary listening skills that you can practice everyday.

Step 1: SET AN INTENTION (to pay attention). This step has 2 parts:

(a) Choose to listen – instead of fading in and out – with a purpose of understanding what the other part is saying and what makes it important to them. This means being curious. Listen for two categories: content and emotion. This means managing distractions. (b) Pay attention. What gets in the way of this? NOISE (see step two) – not external, ambient noise, but your internal noise: errands, emails, work, a pinging phone and social media alerts, “I’m getting hungry.” Setting an intention is a VERY powerful anchor. If you don’t set an intention to listen, you won’t be listening effectively. You’ll get bits and pieces. You might get “most” of it, but you won’t get all of it.

Step 2: MANAGE YOUR “NOISE” (Noise = anything that distracts you)

“Me Too” – identification / projection

“Been There, Done that and here’s what you need to do” – Advice

“I’ll Save you!” – rescue / co-dependency

“Oh, how terrible” – sympathy (having your own feelings and wanting to express them)

“What a stupid thing to do!” or “I can’t believe she’s so upset over something like this!” –judgment

“You are wrong and I know what is right” – authority / wanting to set the speaker straight.

“Who did what to whom, when and why?” – interrogation. You ask questions you think are important and control the conversation.

“Tell me about your childhood” – analyst

“I don’t want to hear this” – censor

Paying Attention means (a) tracking the speaker and (b) tracking yourself. You can’t eliminate your noise, but you can learn to manage it. Notice the noise and then refocus on your intention to listen (This is referred to as the “LISTENING LOOP.” You will navigate this loop a few times while listening to someone for 5 minutes: set intention, focus, notice noise creeping in, manage noise, re-set intention, etc.) When you pay attention, you listen for two things: (a) content; and (b) feelings (consider feelings another category of facts). Noise pulls you away from their story and focuses on your story – e.g. thinking about what you want to say next.

Pro Tip: Being quiet while you wait for your turn to talk is not the same as listening.

Step 3: REFLECT BACK

Remaining quiet as the other person gushes, while you nod your head and then finally say, “I understand” is incomplete. How do you know you understand? How do they know you understand? Maybe you misunderstood something. Maybe their thoughts aren’t organized and they haven’t expressed a thought accurately. The job of a skilled listener could be described as helping the talker talk. By reflecting back (that is, summarizing / recapping both content and emotions), you accomplish:

*Empathy (a powerful tool in negotiation, plus dopamine secretion in the brain by the speaker, who feels “seen” in addition to heard)

*Clarification (“no, that’s not what I meant. I meant . . . ”)

*Verification (“yes, that’s right!”)

*Encouragement (which gets you even more information)

*De-escalation (and slowing down the excretion of cortisol in the brain of the speaker)

How many times have you been in a conversation where the other person repeats themselves over and over again like a broken record? Often this happens because they don’t feel they’ve been heard.

Think of your goal like this: to listen to that other person like they have never been listened to before. You concede nothing by doing this: understanding somebody does not mean you agree with them.

Recap: (1) Set Intention (to pay attention – content and feelings); (2) Manage Noise; (3) Reflection – summarize their story (facts) and emotion (why speaker cares)

Like all other negotiations skills, Listening isn’t a superpower unless you practice it and develop it like honing and toning any other muscle. I have actually been in several negotiations in my legal career where I have demonstrated listening to the party on the opposing side better than their own attorney has. And guess what that makes me?

The most powerful person in the room.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Abstract: History of the handshake, its societal and business uses, its importance in mediation and negotiation, and what lies ahead now that the handshake has become a casualty of Covid-1.

Abstract: History of the handshake, its societal and business uses, its importance in mediation and negotiation, and what lies ahead now that the handshake has become a casualty of Covid-1.

Masks are nothing new. They have been used in rituals and ceremonies dating to 7000 BCE.

Masks are nothing new. They have been used in rituals and ceremonies dating to 7000 BCE. We (Americans and many diverse people in organizations) have borne witness to this moment before: there was a terrible event, we were outraged, we reacted, then it went away. Yet systemic racism hasn’t changed. How can leaders meaningfully respond to racial tragedies? This was the subject of a webinar and

We (Americans and many diverse people in organizations) have borne witness to this moment before: there was a terrible event, we were outraged, we reacted, then it went away. Yet systemic racism hasn’t changed. How can leaders meaningfully respond to racial tragedies? This was the subject of a webinar and

gotiation skills is robust, if I had to pick one above all others, it’s listening – which is both terribly important and terribly underutilized. In the early 2000’s during my initial training as faculty for the Center for Negotiation & Dispute Resolution at UC Hastings College of the Law, I learned a method for teaching Negotiation students cultivated by psychotherapist Judi MacMurray, who granted permission for us to share her methodology. This chapter of my blog is a compilation of her tutorial and my own adaptations and experience with listening over the years. Consider it a step-by-step guide – not just in negotiation, but in everyday life. Like everything else, it takes practice:

gotiation skills is robust, if I had to pick one above all others, it’s listening – which is both terribly important and terribly underutilized. In the early 2000’s during my initial training as faculty for the Center for Negotiation & Dispute Resolution at UC Hastings College of the Law, I learned a method for teaching Negotiation students cultivated by psychotherapist Judi MacMurray, who granted permission for us to share her methodology. This chapter of my blog is a compilation of her tutorial and my own adaptations and experience with listening over the years. Consider it a step-by-step guide – not just in negotiation, but in everyday life. Like everything else, it takes practice: