Episode 3: Not A Penny Less Or Strike Me Dead

Rapport and Haggling (13 minutes to listen)

Episode 2: The Chocolate Negotiations

A Negotiation Appetizer (7 minutes to listen)

Episode 1: Why Are We Here?

Introduction to our podcast (2 minutes to listen)

Freedom of Speech: When the Marketplace of Ideas Crashes Your Negotiation

The “marketplace of ideas” concept of freedom of expression has been around since 1859 and the American philosopher John Stuart Mill. It is based on the same theory of economics that superior products sell better than inferior products: thus, spurious speech will be filtered out while the most worthy ideas rise to the top. It was Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes who, in a 1919 Supreme Court case, introduced the “marketplace” idea into judicial analysis and, since then, it has been repeated by the Supreme Court to oppose censorship and support freedom of thought and expression. It is a powerful idea.

The “marketplace of ideas” concept of freedom of expression has been around since 1859 and the American philosopher John Stuart Mill. It is based on the same theory of economics that superior products sell better than inferior products: thus, spurious speech will be filtered out while the most worthy ideas rise to the top. It was Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes who, in a 1919 Supreme Court case, introduced the “marketplace” idea into judicial analysis and, since then, it has been repeated by the Supreme Court to oppose censorship and support freedom of thought and expression. It is a powerful idea.

Suffice to say: technology and society have evolved since Mill and Justice Holmes so purely preached that the free competition of ideas is the best way to separate falsehood from fact. Is it still relevant? Was it ever a reliable theory?

In recent years, “fake news” has become a pervading paradox to dismiss facts that are disliked over prurient opinion – which then is tweeted and followed and elevated to a point of muting objective fact. Certainly some false information is a product of misinformation posted by regular folks and spread through the blogosphere. But it’s also a new business model: entrepreneurs seek to make money by contriving false information and garnering advertising. Even more disconcerting is the increasingly predominant paradigm of opinions equating to facts with the art of dialectical discourse fading like a watermark on The Bill of Rights, and disrupting our personal lives, negotiations and conflict scenarios.

Has the “marketplace” of ideas crashed, with free speech running amok? Could it simply not withstand the relentless demagoguery of social media, which Mill and Holmes could never have imagined? Founding Father James Madison believed that the First Amendment was the triumph of reason and humanity, over error and oppression. But reason only carries humanity so far and Mr. Madison never signed up for Instagram.

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson teaches three categories of truths: objective truth, personal truth and political truth. He warns against asserting a truth before making sure it’s not just an opinion you desperately want to be true. But I have to ask: if the post by the boy crying wolf surpasses one million views, does the wolf evolve from fiction to fact?

And now to challenge Dr. Tyson: is there such a thing as objective truth? And what happens when the marketplace of ideas crashes in our own back yard, threatening our job, family status, business venture, or peaceful relationship with a neighbor? As a mediator, my long-standing refrain is that there are not two sides to a story. There are actually two different stories. For each party their story is real, valid and “fact.” Philosophers throughout the ages have grappled with the question of objective fact, with varying perspectives. Plato is known for a distinctive view of objective reality. He asserted roughly that the greatest reality was not in the ordinary physical objects we perceive around us, but in what he calls Forms, or Ideas. While Nietzsche did not plainly reject truth and objectivity, he did reject the notions of absolute truth, external facts, and non-perspectival objectivity.

As individuals navigating our own stories, and as a mediator observing, listening and learning the stories (and attitudes about “facts”) of parties breaking through conflict, it is useful to bear in mind that we are not fully in control of our own story. We are interwoven with each other forming and being reformed as we move through the world. As the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has proffered, our actions are constantly woven into the web of others. Embracing this realization can neutralize some of the insidious loneliness (and arrogance) of the singular perspective (fueled also by Confirmation Bias – see June 2016 post on this blog) of our subjective narrative . But it requires curiosity – or at least some unfulfilled need to move forward (e.g. “If I can’t negotiate the cost of COBRA coverage and a positive reference, I risk future job opportunities and replenishing my child’s medication, which is essential to my the livelihood of my family.”).

The fact that one is engaged in conflict (and the untangling of it – through mediation or negotiation) at all, while uncomfortable for many people, is very promising because conflict is a signal that something must change. The best advice I can offer when absorbed in a negotiation with another party whose facts differ from yours is to not place too much importance on them.

What?!

Yes, I repeat: Do not place too much importance on facts in a negotiation.

Peace-making strategies based solely on rationality and logic are limited. And remember that memory is faulty (including yours); we edit and adjust past events to fit the current situation. Instead, find out what emotionally matters to the other side, and how your stories are interwoven and informing one another. Ask what you each might lose if you don’t reach a deal.

Our nation’s “marketplace” of ideas may be in crises. But like our own individual (or organizational) conflict, I choose to believe the disruption is not only productive, but necessary for progress – which takes time, is not neat and linear, and happens in increments. When you find yourself mired in mess, it’s time to get excited because you are a player in a process that is ripe for a breakthrough.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

The Law of Conformity – Conflict Lessons from 2021

Also known as the 95 percent law, Peter Sage calls it the law of conformity. If you hang out with nine motivated, go-getting, positive individuals you’re going to become the tenth. If you hang out with nine recreational drug users, you’re going to become the tenth. The only other outcome is that you leave the group. Environment will trump intentions just about every time. Thus, we need to choose our associations carefully.

2021 has been a difficult year for dispute resolution, human behavior and psychology, mediation, and for me personally. Toxic polarization on a national level was fractal within our local communities. The politicization of the Covid vaccine, cancel culture, a movement to mistrust our voting system, all opinions represented as incontrovertible fact . . . we have witnessed amygdala hijack and galvanization at a national level that is playing out in our own back yards. I am known for reminding people, at some point during a mediation, that if our rearview mirror were as big as our windshield, we’d never get anywhere. That is, when people stay stuck in the past, it’s impossible to heal from conflict and move on with life in a new, positive direction. Mediators, in general, are forward thinking and part of our job is to influence the parties to adopt a forward thinking approach – after a healthy space is permitted for sharing each story (no, not two sides to the same story: two different stories) and validating perspectives and feelings. And then it’s time to get to the business of moving on. But this year, I have noticed a marked difference in people’s willingness and ability to move on. It’s as if they insist on remaining in that wounded, alienated space. I will even admit this has caused me to suffer a crises of confidence in my considerable legal and mediation skills of 24 years. “Maybe I’m not good at this anymore,” I started to wonder.

In the meantime, this year found me occupying a volunteer board of directors role that I mistakenly interpreted as community service when I agreed to take it on in late 2020. More that that, I was seduced by a Siren’s call of being “just” the right person that was “needed” at “just” that moment in time. Instead, it turned out to be a highly politicized environment of deeply rooted sexism and bullying. I was absolutely convinced that my training in the behavioral sciences and experience as a mediator (not to mention unflagging optimism) could turn around a toxic situation and reshape behaviors. So I tried harder. But in trying harder, what I failed to see is that the Law of Conformity was taking hold and I was becoming more entrenched with the bullies. The more I stood up to them, the more I was perceived as one of them. By the time I realized this dynamic, it was too late. My heart had been crushed and my reputation (and relationships) tarnished in the process. How did I fail to read the room and calibrate my approach? I was like that determined ant marching purposefully North on a mission of equity, diversity and inclusiveness, but unaware that each footfall tread on the back of an elephant heading South. Reflecting back now on a year of lackluster peace-making in mediations and the 95 percent rule causing my altruistic efforts in a volunteer position to be wildly misunderstood, more questions cropped up for me:

Why do conflicts erupt so easily and take over people?

Why are some people more open to others?

Why do facts matter so little in conflicts?

According to social psychologist Mari Fitzduff, our “wars” today appeal to instincts and savage emotions, not rationality. They are about identity, inequality and exclusions. We have feelings and instincts to serve our survival as human beings, through (1) DNA, (2) hormones (dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, adrenaline, testosterone) and (3) environment (see 95 percent rule, above). In fact, Fitzduff discusses a gene variant called the DRD4-7R which affects dopamine – people with it are more likely to be open-minded and to enjoy pleasure from variety, novelty and diversity. fMRI scans* show how variances in biology and genetics influence differences in attitudes and beliefs: conservatives have larger amygdala structures (that is, the emotions / fear center of the brain) and higher startle responses (as shown in fMRI) than liberals; they are more likely to support capital punishment, stricter immigrant controls, more military spending. People at the lower amygdala end are happier in general (and experience less startle response).

Brains differ on a continuum in responding to new information, uncertainty, fear, and strangers. Biologically, humans have evolved for cooperation – but only for some people (in-group versus out-group – testosterone and oxytocin – the same hormones that warriors had: increase sense of belonging and reduce fear. They also promote ethnocentric behavior and increase suspicion and rejection of others outside the tribe. Oxytocin binds us, but also blinds us). Fitzduff opines that the need to belong is a major driver of war. Most people need to belong more than they need to be right. When beliefs are contradicted, fMRI showed an increase in emotion (amygdala response), but no increase in cortex reasoning. When people are in conflict, they like things to be simple and it is more likely that nuanced categories of people get hurt ( because they are confusing). Thus, Fitzduff cautions against complexity, novelty and over-reliance on facts during conflict.

So, what are my take-aways from such a destabilizing 2021 in my personal and professional life?

(1) Choose my environment and my company carefully (consider honestly “do I belong here?” rather than falling prey to recruitment techniques); recognize that an environment will change me, not the other way around; while I am a passionate proselytizer of diverse viewpoints and believe that diversity makes us stronger, I need to choose a positive environment to support my positive agenda;

(2) Instead of being drawn into a negative mindset or peer group, be willing to walk away from a toxic situation; don’t feel obligated as a representative of “all women in leadership” or some such lofty perception of my relatively unimportant role;

(3) I am an empath, which has served me very well in my life and profession, but empathy fatigue is real; it’s time for some detachment;

(4) Other people’s opinions of me are truly none of my business;

(5) Commit to self-mastery so that when things devolves into chaos, I can retain my own equilibrium; when conflicts arise, slow down and keep things simple.

In the words of Seneca the Younger:

“The gem cannot be polished without friction, nor man perfected without trial.”

I have to believe that I will shine brighter and be a more perfect human as a result of 2021.

*a word about neuroscience and fMRI scans. Even as someone who cites consistently to brain science, I bristle at how fashionable this has become in the mainstream media. The media loves to cover new fMRI results, and the business world is hungry for the consumer brain to be decoded. Unfortunately, studies are often tiny because of the high costs of running the machine and interpreting the results and the data can be tough to interpret. A 2009 study of a salmon, for instance, showed the “fish’s brain exhibited increased activity for emotional images.” The only problem? The fish was dead.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

“What Should I Wear?” – Making Choices and Online Dispute Resolution

Steve Jobs famously wore the same black turtleneck, blue jeans and New Balance sneakers every day.

Do you know why (bonus points if you can name the designer of his turtleneck  without Googling it. Hint: it wasn’t off the rack from Gap. Answer below)? It was to minimize his number of daily decisions, especially early in the day.

without Googling it. Hint: it wasn’t off the rack from Gap. Answer below)? It was to minimize his number of daily decisions, especially early in the day.

Choices are wonderful, right? We demand choices because we want a wide variety of them – or so we think. Many successful individuals like Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, and Albert Einstein understood that less time spent on making minor decisions meant more brainpower and time for everything else. Researchers have actually studied the effect that making too many decisions can have on our lives. And what studies repeatedly show is that our capacity to consistently make thoughtful decisions is finite. This means that when you use your brainpower earlier in the day (e.g. deciding what to wear), you’ll consequently have less of it at 4pm when you are trying to decide which of the 50 unanswered emails in your inbox should take priority. Show of hands: how many times have you and your spouse / partner had this exchange: “What do you want for dinner?” “I don’t know. What do you want?” “I don’t know, I’m asking you!” “I don’t really care.” “[Sigh] That’s not helpful!!” Well, it’s probably about 6pm and both of you have made countless little choices throughout the day (plus, you’re hungry!), and your brain is pooped. It’s called “Decision Fatigue.” Highly successful individuals actually make fewer decisions because less time spent on making thousands of trivial decisions means more brainpower and time for the big inspirations and the important choices.

What does this have to do with mediation or ODR? Consider the “old days” when parties booked their One Big Day of mediation well in advance, and planned for a full 8-12 hour (or longer) day mediating their dispute in person in a brick and mortar conference room. It was exhausting for everyone. By the time the mediation process got around to generating real options, concessions, and resolutions one issue at a time, most likely a couple of hours had already elapsed with ground rules, opening statements, creating an agenda and defining issues, and moving past positions to interests. The Decision Fatigue clock was already ticking away, and with each passing minute, the ability to make thoughtful decisions was eroding. By hour eight, the situation could be precarious in many aspects: either parties became frustrated and could walk away that they still didn’t have a deal; or parties could make hasty decisions just to be done with it, and end up with regrets. Certainly, skilled mediators worked in breaks and nourishment, but it may not have been enough to equalize the marathon and fully rest the mind.

Now that many (most?) of us mediators conduct mediations via Zoom or similar video-conference tools, the process has evolved. We don’t spend 8-12 hours on a single Zoom mediation. Zoom has magnified the impracticality of doing so, just by virtue of the incapacity of the human eye and mind to stare at a square on a screen for more than about 60 (90 tops) minutes at a time. At least in my practice, I now break up mediations into shorter segments over the course of days, and combine the synchronous Zoom sessions with asynchronous email or phone calls. For all the shortfalls of Zoom brings to the mediation and negotiation process (more difficult to build rapport, make eye contact, see and mirror body language, notice micro-expressions, and generally have “skin” in the game the way people do in person), one of the pitfalls (“Zoom fatigue”) has assisted my mediations by forcing us to break the process down into smaller pieces, incorporating meaningful breaks of hours or days, and thus avoiding the decision fatigue that is inevitable after a long day of mediation. This can, of course, lead to even more practical and durable agreements, and reduce morning-after regrets. Importantly, this benefits not just the parties but the mediator: deep listening, re-framing, thoughtful communication and ensuring fairness at all times is exhausting.

We are faced with countless choices each day. A few might be simple; many are complex. Layer on top of the average day a stressful dispute, and the Decision Fatigue clock can run at double time. The realities of online dispute resolution offer built-in “limitations” that permit parties (and the mediator) to fend off decision fatigue and be better positioned for meaningful decisions that can truly allow them to find resolution and move forward.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

*Japanese designer Issey Miyake designed the iconic black mock turtleneck for Steve Jobs. Jobs commissioned Miyake to design a uniform vest for Apple employees (an idea that got him booed off the stage) after a visit to Japan in the 1980’s when he visited Sony and saw the uniform vests worn by Sony employees.

*Pictured above: Issey Miyake “Pleats Please” black turtleneck jumper with square shoulders

The Power Of Imagination

In his book SAPIENS, A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari affirms that the greatest differential held by Homo Sapiens in the evolutionary process is due to their imagination capacity: the ability to create fiction and believe in common myths. Harari points out that a large number of strangers may efficiently cooperate among themselves when they believe in the same myths. He proffers that such assumption applies to both the Modern State and to ancient tribes, where the shared myths exist only in the collective imagination.

In his book SAPIENS, A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari affirms that the greatest differential held by Homo Sapiens in the evolutionary process is due to their imagination capacity: the ability to create fiction and believe in common myths. Harari points out that a large number of strangers may efficiently cooperate among themselves when they believe in the same myths. He proffers that such assumption applies to both the Modern State and to ancient tribes, where the shared myths exist only in the collective imagination.

Anthropologists think that for about 190,000 of our first years as Homo Sapiens we mostly used imagination to resolve disputes and solve problems. On the southeastern African savannahs, small migrating bands of hunter-gatherers sat around campfires and combined their imaginations to invent the best ways to survive. While they did not invent the fire that warmed them, cooked their food, and protected them, they did invent an impressive list of ways to use it. Around those campfires humans used their collective imaginations and their long-term relationships to survive and develop even better ways to live.

Yet, somehow modern adult humans have stifled these interaction skills that promoted our success as a species, not in small part to due three distinct industrial revolutions throughout the centuries and the technology explosion, which automates process and decision-making and purports to make everything “easier.” But these Artificial Intelligence and other digital modalities designed to “simplify” things may come at the cost of eroding the human cognitive process of imagination. After all, if a packaged solution is built in to the App, why continue thinking through alternatives? It is different in children, who frequently engage in pretend play with one another. Pretend play activities help children to adopt the role of “somebody or something”else. This modality of play is essential not only because it fires up their creativity and imagination, but also because it helps to develop critical skills such as communication, empathy, and socialization. Through this type of play activity, kids can learn different talents and attitudes. They will also become adept at expressing their feelings and build language and motion skills.

Clearly, the beliefs and the capacity for imagination were decisive for the formation and organization of human society (for both bonding and its opposite: divisiveness). In contemporary history, trust is placed on fictional constructs, such as market, economy, the dollar, institutional prestige (a word, in original French which actually means to deceive), corporations, among others, which owe their validity, efficiency and legal personality to a social consensus based on fiction. Commerce, empires and universal religion are fictions that led us to today’s globalized world (and are responsible for many wars). Individuals and groups who share a mythology or belief system become an in-group that perceives shared values and goals. They trust each other and will work collaboratively to achieve goals and solve problems.

Imagination or inventing a fiction also serves as an important tool to boost confidence, increase one’s aspirations, and willingness to even enter into a negotiation at all. Plenty of research has shown that negotiators with strong alternatives are able to secure a more satisfying agreement. But lesser-known and discussed research suggests that you don’t necessarily need to have an attractive alternative, you just need to think that you do. Mentally simulating an attractive alternative can make you a better negotiator. From the neuroscience angle, imagining a workable alternative will slow the brain’s cortisol spiking associated with feelings of helplessness in the planning stages and actual negotiation itself, thus diminishing the prospect that the brain’s executive functioning will shut down. Athletes have engaged the imagination for years as part of training and competition: using visualization techniques, they imagine in their mind’s eye the perfect trajectory (of a free-throw, an approach shot with a 9-iron to the green, a tennis serve) before performing the real thing. Vividly and specifically imagining and believing it can actually make it happen.

Why is this useful? Well, in short, imagination is an incredibly powerful evolutionary process for invention, social bonding, and problem solving. Understanding the anthropological, behavioral economic, and neuro-scientific importance of imagination; making an effort to discover other people’s beliefs and fictions with genuine curiosity (you don’t have to agree with them); and relating those beliefs to the way people make decisions can be an incredibly effective tool in negotiation and dispute resolution. As a mediator, at some point in any given mediation, I am known to pose a question to the parties that begins with “Imagine if . . .” and it is remarkable how this simple framework can free the mind and emotions from staying stuck in their own narrative and can break through perceived impasse to hatch and explore untapped possibilities.

As written (and performed) by Gene Wilder in his role as Willy Wonka in the 1971 film Willy Wonka And The Chocolate Factory:

There is no life I know

To compare with pure imagination

Living there you’ll be free

If you truly wish to be

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Negotiation and The Magic of Story

Early in my legal career I found myself in a typical settlement negotiation with opposing counsel in a case involving an employee suing for wrongful termination. We had been at the table for a couple of hours cautiously trading information, each attempting to persuade the other to see how the law (or a jury) would favor our respective clients, and why our negotiation demand was reasonable and meritorious. At one point, we seemed stuck, and, at least in my mind, it appeared as though we would leave the table that day without a deal. The other attorney, who had quite a bit more experience than I did, suddenly announced, “Let me tell you a story.” Without waiting for permission, he launched into a narrative about negotiating for a rug while on a trip visiting Istanbul. I set my pen down and settled in to hear him out. Where was he going with this? And how would the story end? He had my attention, and I always love a good story.

Early in my legal career I found myself in a typical settlement negotiation with opposing counsel in a case involving an employee suing for wrongful termination. We had been at the table for a couple of hours cautiously trading information, each attempting to persuade the other to see how the law (or a jury) would favor our respective clients, and why our negotiation demand was reasonable and meritorious. At one point, we seemed stuck, and, at least in my mind, it appeared as though we would leave the table that day without a deal. The other attorney, who had quite a bit more experience than I did, suddenly announced, “Let me tell you a story.” Without waiting for permission, he launched into a narrative about negotiating for a rug while on a trip visiting Istanbul. I set my pen down and settled in to hear him out. Where was he going with this? And how would the story end? He had my attention, and I always love a good story.

He unspooled his tale about how the rug merchant served him tea, and they sat and talked about their families, and how he thoughtfully looked through the inventory, pausing to ask about various rugs, with the merchant proudly explaining in detail the craftsmanship of each of them, before narrowing in on one of them, and then more tea was poured, and the haggling over price eventually developed. He recounted of how he and the rug merchant went back and forth on price for a while, until they finally reached a number that they could both agree upon. At that point, he told the merchant (about an hour into their repartee), “Yes. That is a good price. That would, indeed, be a good price for me. But, you see, this rug is actually for my son. My son is just starting out in his career and asked me to select a rug for his new home with his new bride, and he is on a less forgiving budget than I am. So, we need to reach a price that is good for my son,” and the negotiation continued “on behalf of his son.” It was actually a charming little story and we were both smiling as it drew to a close. We picked up where we left off with our own negotiation, and were able to each find more wiggle room for a deal that would work “for our clients,” even if the numbers we had reached before story-time worked for us.

What I did not understand at the time was that my more seasoned counterpart knew how to cast a storytelling “spell” to lubricate the gears of deal-making. Joshua Weiss, PhD and co-founder of the Global Negotiation Initiative recently spoke about the power of story in negotiation. – which is often more about creativity than it is about compromise. Stories are a way of assimilating creativity into a negotiation, and can be pivotal for a variety of reasons:

*Good stories create a sense of connection. When someone says, “I have a story to tell you . . . “ people are intrigued and more open to listening. They invite the listener into the story, making them more curious and open to learning – “What else might be going on here that I didn’t think about when preparing?” They can also convey complex ideas in ways that are easy to grasp.

*People are less likely to interrupt a story than they are you listing all the reasons for your demands. It also makes them wonder, “What will happen next?”

*Stories are extremely effective at building rapport and tend to reveal commonalities, which makes it much easier to transcend positions and discover underlying interests. They can also help save face when a party to the negotiation has gotten themselves in a trap with their own behavior, and can break impasse.

*Stories transcend different learning styles, convey lessons, and provide relatable examples.

*Stories are disarming and nurturing – reminiscent of childhood and a parent reading a bedtime story. Importantly, they often come from an outside perspective, which can help foster trust. That is, you aren’t making it about you. Oddly, even when you are telling a story about yourself, it seems to come from someplace else.

*Stories are excellent memory aids, and easier to recall in tense moments than data.

*Stories are normative. They comfort people by reminding them that this isn’t the only time someone has dealt with this kind of a challenge. Others have figured it out, and so can we.

*Stories are hard to argue – they can’t be debated or discredited by the other side. This is important because, although you can’t change people’s minds, in a situation where the parties hold two opposing ideologies, telling a story might cause them to change their own mind.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the internal negotiation: what story are you telling yourself about the negotiation, and how might that be holding you back? Can you change your story? For example, are you telling yourself, “I have no power in this negotiation”? Examining your own story can help level power imbalance (consider the example of a single company that has the piece of very specialized equipment you need. Can you improve your alternatives in some way you have not considered and that the other party, who thinks they have a hold on you, also has not considered?). Sometimes it is worth consulting with an outside third party to check your assumptions and perspective.

The bottom line is that stories are universal. Every culture on the planet has a history of stories. Story-telling is ancient; there is no stronger connection between people. So, next time you are preparing for a negotiation (or even a difficult conversation with somebody), have a story or two in your quiver that you can share at the right moment to build rapport, ease a tense moment, break through impasse, or spur the other side’s sense of curiosity so that you are both more open to listening and learning from each other.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal

Sedition and Neuroscience: The Myth of Rationality

Abstract: Events in our Nation’s Capitol not even a full week into 2021 have sparked numerous articles, discussions, and questions about the crises of our country, the divisiveness of its people, and human nature in general. This Primer in Neuroscience, Emotions and how they impact decision-making and human conduct when in crises may help demystify the myth of rationality to gain an understanding of why people in conflict behave the way they do.

Abstract: Events in our Nation’s Capitol not even a full week into 2021 have sparked numerous articles, discussions, and questions about the crises of our country, the divisiveness of its people, and human nature in general. This Primer in Neuroscience, Emotions and how they impact decision-making and human conduct when in crises may help demystify the myth of rationality to gain an understanding of why people in conflict behave the way they do.

As a mediator, I work with people in conflict – and who have been in conflict long enough that they have decided they need my help. I am not a neuroscientist. But a basic understanding of the crossover of neuroscience and dispute resolution can lead to new breakthroughs working with disputing parties in mediations, and also in engaging with people generally in the world – especially now, especially when crises is the status quo for so many people.

So, first things first: when people are in crises, the brain secretes cortisol. Increased cortisol levels impact:

Decision making

Risk assessment

Rational cognition

Focus

“Working memory” (how much information a person can hold, process and use at any given moment)

Perception of “Threat”

The emotional and physiological response is by and large the same for both physical threats (a snake) and emotional threats (“she’s going for full custody of the kids”), and the cognitive response toggles between 3 fundamental levels of functioning: Reptilian (fight or flight, the neural networks related to fear/survival – a very durable network); paleo-mammalian (social bonds, decisions); Neo-cortical (high level executive functions).The exercise of law, engineering, accounting, science, etc. is a neo-cortical activity, but decision-making is a sub neo-cortical activity. So, when someone suddenly shifts position and we think they are acting “irrationally,” it’s that a different part of the brain (the non-executive part) has taken over. The same can be said when the opposite happens (as has become common with accusations of “fake news” and abounding conspiracy theories of late): someone refuses to shift their mindset, even faced with objective facts to discredit their original opinion or position (see this Blog’s 6/1/2016 piece on “Confirmation Bias”). Even the common act of getting angry at one’s kids is a core relational theme (more on that below) leftover from the Reptilian brain (“my progeny is in danger and I need to act”). But if the Executive / higher brain reappraises in time, it can ask whether anger or fear or maligning the other person is really the appropriate response to the situation. Think of how different our interactions might be, and how many explosive situations might be defused, if more of us recognize when this is happening.

The brain employs a 3-goal system:

Avoid: sticks (threats, penalty, pain)

Approach: carrots (rewards)

Attach: to other people (bonding)

Although we are wired to cooperate socially and to bond, we are very reactive to threats, and the brain has a Negativity Bias: this means the Sympathetic nervous system lights up like a Christmas tree at even a whiff of a threat, and that “sticks” are more impactful than “carrots!”

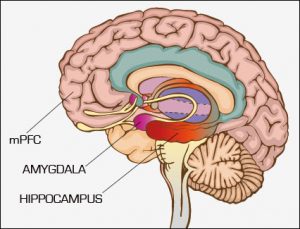

Consider for a moment your Amygdala hippocampus system (labeled in the image to the right). It is primed to label experiences negatively and will flag a negative experience prominently in the memory. With ambiguous communication, this means that IF a negative inference can be made, it WILL be made, in lieu of a positive interpretation. The negativity bias is so robust that it takes 5 positive interactions to undo a single negative one. Thus, people will do more to avoid a loss than realize a gain; and the Avoid system is routinely hijacking the Approach and Attach system. The result of threat reactivity is that people in a dispute overestimate threat and underestimate opportunity in their initial appraisals. If nothing or no one (such as a mediator) helps them reappraise that the snake is a stick, the brain continues to pump cortisol and reinforce stress. This happens in everyday situations, not just in national news when a mob of thousands storms the Capitol (is anyone remembering an argument with your spouse or significant other at this point?) The cost of not steering people towards reappraisal is that actions and decisions while feeling threatened lead to over-reactions, which causes other people to feel threatened, and a vicious cycle ensues. The Approach system is inhibited, thus limiting options and opportunities.

the image to the right). It is primed to label experiences negatively and will flag a negative experience prominently in the memory. With ambiguous communication, this means that IF a negative inference can be made, it WILL be made, in lieu of a positive interpretation. The negativity bias is so robust that it takes 5 positive interactions to undo a single negative one. Thus, people will do more to avoid a loss than realize a gain; and the Avoid system is routinely hijacking the Approach and Attach system. The result of threat reactivity is that people in a dispute overestimate threat and underestimate opportunity in their initial appraisals. If nothing or no one (such as a mediator) helps them reappraise that the snake is a stick, the brain continues to pump cortisol and reinforce stress. This happens in everyday situations, not just in national news when a mob of thousands storms the Capitol (is anyone remembering an argument with your spouse or significant other at this point?) The cost of not steering people towards reappraisal is that actions and decisions while feeling threatened lead to over-reactions, which causes other people to feel threatened, and a vicious cycle ensues. The Approach system is inhibited, thus limiting options and opportunities.

*Take away: it is more likely that people will deviate from rationality than be consistently rational. Recognize how powerful it is to know how to identify which part of the brain is working, when and why. Mediators use active listening, reframing, and timing of breaks to help the people’s brains reappraise and stop the vicious cycle. So can you, with practice . . .

A brief word on the role of emotions:

Here is what I have learned from my 30+ hours of training from the Paul Ekman Group and Dr. Ekman’s book Emotions Revealed: Core Relational Themes inform how we deal with people in the world. Our cell assemblies have, over thousands of years, created a sturdy emotion alert database. This database serves an important purpose:

FEAR protects us; our lives are saved because we are able to respond to threats of harm protectively, without thought.

DISGUST reactions make us cautious about indulging in activities that literally or figuratively might be toxic.

SADNESS and despair over loss signals to others that we may need help.

Even ANGER is useful; it warns others, and us as well, when things are thwarting us.

Probably the most important nugget I learned from Paul Ekman’s book Emotions Revealed is the concept of the Refractory State – this is the time during which our thinking cannot incorporate information that does not fit, maintain, or justify the emotion we are feeling. For example, have you ever tried to apologize to someone while they are still mad at you? It’s futile. A Refractory State lasts an average of 20 minutes, and the person experiencing the strong emotion simply cannot take in any new information until the refractory state has passed. Recognizing a refractory state can be key in terms of what you do next. When you identify the refractory state, understand that the Executive level of the brain is not operating during this refractory period – and it may be wise to step away from the immediate situation to take a break.

Take-Away: Rationality is a myth. Instead, human behavior and circumstances are predictably irrational (the title of another book I recommend, by Dan Ariely). Rational choice theory is but one approach to conflict, and not necessarily the most effective one where emotions, distrust and suspicions simply cannot be suspended even among people of good will and reason. With even a simple understanding of neuroscience and emotions, anyone can learn to manage the human experience effectively and without relying upon faulty and insufficient ideology of how one “should” behave or “should” approach conflict and decision-making.

Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal